This video was made by interviewing a group of commoners who attended to the first public meeting of the European Commons Assembly in Brussels, 15-17 November, 2016. They reflected about how neoliberalism shape cities as places for tourism, gentrifying and dismantling the cooperative environment of the neighborhoods; as well as how commoners build alternatives by sharing responsibilities in designing a different framework.

The video is part of our series of video presentations on the different thematic work areas of the ECA. We are also sharing our proposal on the Urban Commons in the text below. Finally, you can also read and comment on the proposal on the Commons Transition Wiki.

Urban Commons

A proposal by David Gabriel[1] for the European Commons Assembly

Background

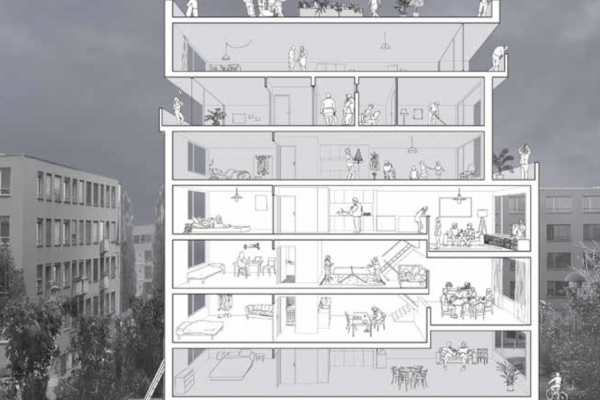

Europe is one of the most urbanised places in the world. Actually, more than 75% of the European population lives in cities. Daily life in cities has combined with the historic struggle of inhabitants to create urban commons. Many groups across the EU reclaim their urban commons, like public space or housing, and try to create new ones. Recently, several movements have been fighting for the right to housing and the right to the city in Europe. In this way, urban commons stand as alternatives to speculation, gentrification, and enclosure in cities.

Urban Commons Issues

- Housing

- Public Space

- The right to the City

- Social facilities

- Policy without school segregation

- Inclusion of the migrants and refugees

- Localizing human rights

- New Municipalism

Practices of urban commons

One of the main ideas reclaimed by the urban commoners is the Right to housing and the Right to the City. The first formulation of a right to the city dates back to Henry Lefebvre during the 1960’s. Since then, networks and civil society organizations have defined “the right to the city as the equitable use of cities according to the principles of sustainability, democracy, equity and social justice. It is a collective right of the inhabitants of these cities, especially for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups who gain legitimacy of action and organization based on their use and customs with the objective of achieving, in practice, the right to free self-determination and an adequate level of life” (definition of the Global Platform for the Right to the City). The occupation of public space is also a new practice of urban commoners, with important consequences in Egypt (Tahrir), Turkey (Taksim), Spain (15M), the United States (Occupy Wall Street) and France (Nuit Debout). Nowadays, many urban commoners are debating about the use, role and importance of public space in the exercise of democratic rights and in ways of challenging capitalism.

Actors involved

Inhabitants, citizen and theirs organizations are involved in the right to the city movement and also networks, foundations, and multilateral organizations. One strategic orientation of the social movement is to achieve alliances with the local authority and networks of cities. The following organizations are some examples:

- Europe: European coalition for the right to housing and the city

- Spain: Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca / iniciativa legislativa Popular por la Vivienda Digna

- Belgium: Habitat et Participation

- England: Radical Housing Network

- France: Droit au Logement / Coordination Pas Sans Nous / Atelier Populaire d’Urbanisme

- The Netherlands: Bon Preaire Woonvormen

- Portugal: Habita – Colectivo pelo Direito a Habitaçao e à Cidade

- Turkey: Istanbul Urban Movements

Urban Policy and the EU

The European Union has no formal authority over urban policy. But given the crisis of the European Union, the cities could become the new scale to implement European policies and to create democratic relations among the citizens. The former European Parliament already called for an Urban Agenda for the EU in 2011. During the Netherlands presidency of the EU in 2016, member states, cities and the European Commission signed a new political agreement – the Pact of Amsterdam – to cooperate in four fields: air quality, housing, inclusion of the refugees and migrants, and urban poverty. Presently, civil society and citizens are not involved in the definition and implementation of the new urban agenda. Nonetheless, the urban common process could be a way the co-produce and implement the NUA.

Supporting and scaling urban commons

Each inhabitant or citizen could be involved in protecting and developing the urban commons. To reinforce the movement, we need to create new relations with the inhabitants and communities, particularly with the people who live in the popular neighborhoods. Community organizing and advocacy planning could be useful methods to rely on. We also need to propose social leader trainings focused on urban commons issues. The articulation between local, national and regional levels is also decisive in scaling up the local campaigns and sharing knowledge. With the institutions, we must re-open the debate around planning theory.

Institutional change

Introducing urban commons in the European urban agenda is the first difficulty. A new alliance between social movements, progressive cities and some European deputies would help. To put the EU agenda into practice, the issues of governance of the urban commons are central and need to include the citizens and the civil society. We are aiming at a cultural change of the European, national and local institutions.

Resources

We need money, methodology and human resources. Concerning methodology, we must share our different practices like community organizing, chartering, advocacy planning, and occupation of spaces. Finally, we need a European center for training new organizers with various capabilities (emotional, relational, rational, etc.)

[1] David Gabriel (Grenoble, France) contact: asso.planning@gresille.org